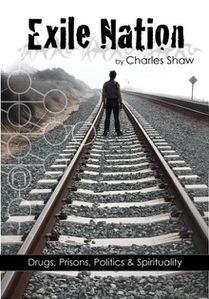

A new Book : Exile Nation

from http://www.realitysandwich.com/exile_nation_chapter_one_dead_time

"EXILE NATION tells the dirty story none of us really wants to hear. But we all should be listening. Author Charles Shaw 'did time' in prison and lived to write about it. The antiquated and terrible system he describes is Dickensonian. Like Dickens, Shaw offers a metaphor for many of the ills that infect our economy and society. And screams for change." - John Perkins: New York Times best-selling author of Confessions of an Economic Hitman and Hoodwinked.

"Brilliant. The most powerful indictment of the prison industrial complex system I've yet come across. I'm in awe."

- David Korten: Activist, Author - When Corporations Rule The World and The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community.

With this explosive first chapter set in Chicago's infamous Cook County Jail, Reality Sandwich kicks off a year-long exclusive series, the publication of Charles Shaw's Exile Nation: Drugs, Prisons, Politics & Spirituality. The entire text of the first chapter will remain posted through the holidays, and smaller excerpts will begin to appear weekly in January 2010 with Chapter Two - "Hotel Hell." Please visit the Exile Nation home page to learn more about the book, read the Table of Contents and the Introduction, and keep up to date with news and developments. Each excerpt and chapter will also be available for download in easy reading, print ready PDF files. (download PDF of Chapter One)

~~~~

PART I - MIND

"One reason for the new penology is a revision in the concept of poverty. Terms like the "underclass" are now used to describe large portions of the population who are locked into an inescapable cycle of poverty and despair. Criminal justice managers (emphasis added) now group people by various collectives based on their racial and social characteristics. Rather than seek individual rehabilitation they are oriented toward the more realistic task of monitoring and managing intractable groups. The fact that the underclass is permanent leaves little hope that its members, many of whom are in the correctional population, can be helped. Penology then stresses the low-cost management of a permanent offender population."

--Larry Siegel, "Criminal Justice Update," Fall 1993, West Publications.

"When a truth comes upon the earth, or a great idea necessary formankind is born, where does it come from? Not from the police or theattorneys, or the judges, or the lawyers, or the doctors. Not there. Itcomes from the despised and the outcasts, and it comes from the jailsand prisons. It comes from the men who have dared to be rebels andthink their thoughts, and their faith has been the faith of rebels."

--Clarence Darrow

~~~~

Chapter One: "Dead Time"

July 7, 2005 - Good Morning

It is 4:30am on tier 1A of Division 5 at the Cook County Jail in Chicago, Illinois, and Donald "Frosty" Rogers stands alone in the day room, staring at the clock high up on the wall. The room has a distinct chill, and barely a sound rolls through the deck as Frosty absentmindedly rubs the faded tattoo on his left arm, which reads, "No Mo' Pain."

He is 59, bald, with espresso brown skin and a bleach-white beard that snakes downward from his ears to wrap around his chin and mouth. Spilling out from a sleeveless white T-shirt, his well-molded, densely packed upper-body shames men half his age. He smiles a toothless grin, and to keep warm he begins to circle his arms repeatedly out before him, the fist of his right hand impacting over and over with the palm of his left, soft and rhythmically. Thak. Thak. Thak. Frosty hears something and looks over at the darkened security bubble. Inside the unit guard is reading yesterday's Sun Times. Without looking up from his paper, the guard waves his arm, reaches over blindly to an archaic control panel, and begins pushing buttons.

A series of stark metallic pops like a row of demolition charges puncture the silence, racing around the tier as one after another the magnetic locks on the cell doors are released. A moment or two later, disheveled inmates clad in dirty brown scrubs with "CCDOC" emblazoned across the thigh and back slowly make their way from the two decks of cells situated above and below the day room. The inmates congregate around three stainless steel picnic tables and wait, heads propped, half asleep, until they hear the clang of the outer security door, indicating that the breakfast cart has arrived.

When the signal comes, the hungry inmates circle the doorway in muted homage to Pavlov, hoping to catch a glimpse of the day's offering. Two indolent gang-bangers in hair nets slowly begin to stack hard plastic trays one atop the other to a height of five feet, intentionally dragging out the process simply out of schadenfreude. Each tray has a small amount of dry cereal, a nondescript juice box, a small glop of cold potatoes, and a piece of bread.

Frosty hangs by the inner door waiting for the guard to buzz in the food so he can begin distributing it. Acrid smoke from hand-rolled Top menthol cigarettes hangs in the air, and the have-nots begin to case the haves. Hustling commences.

"I got a juice fo' a roll, juice fo'a roll," an inmate shouts. "Come on ya'all, who goan gimme a square, mang?"

"Got chou, man," another says, flipping him a hand-rolled cigarette, or "roll." Commercial cigarettes, "squares," are expensive and in short supply. The have-nots are relentless in their begging, so people are discreet about revealing their cache anywhere near the day room.

The inmate who just received the "roll" puts it in his mouth, tips his head all the way back, lights a match, and slowly connects the two dramatically before sucking smoke in deep and blowing a cloud towards the halogen lamps high above, eminently satisfied with the day's first infusion of nicotine. In a lock-down situation this little steam valve sometimes makes all the difference in the world in preserving order.

"Only one more month, ya'll," he says, alluding to the jail-wide smoking ban that will go into affect on August 15th.

"Sheeeeit. This mufucka goan go live, Joe," replies the one who gave him the cigarette. "Last time they tried that shit, they were takin' White Shirts hostage on Division 9. It got buck ass wild up in heah."

An old black dude who called himself "Sensei" stares down through his bifocals at a chess board and comments, "It is an inveterate habit, Grasshopper."

"A what?" dude says.

"Consider it a favor from the State," Sensei mumbles, while scrutinizing the chessboard.

Although rarely discussed, inmates are visibly disturbed by this change in policy. It is true that they attempted once before in the late ‘90s to ban smoking, and there were indeed riots. It didn't even last a month. This time, they meant business, because this time it was all about cutting back on health care costs, not because they were particularly concerned about our health. For the preceding two months before the ban went into effect, every two weeks the amount of tobacco an inmate could purchase through the commissary was halved, and tips on how not to go berserk after you quit smoking were posted on every tier.

Frosty grabs a breakfast tray and stands in the inner doorway. Next to him on the floor is a milk crate filled with small cartons.

"All right, line it up!" he shouts. "Fin Ball, then Neutron, then One-Love!"

The fifty some inmates begin to order themselves sequentially into three different groupings based upon their gang affiliation, or lack thereof. In the front of the line are members of "Fin Ball," a name for the five allied gangs of the largely South Side "People" Nation-the Vice Lords, Latin Kings, Blackstone Rangers (or "P-Stones"), Black Mafia, and Insane Popes. These five gangs who bound together in the 1970s to protect themselves against the domination of "One Love," or gangs from the West Side "Folks" Nation, who are dominated by the laws of the Gangster Disciples, the single largest gang in the Chicago milieu.

Sandwiched in between these two opposing armies are the "Neutrons," or the non gang-affiliated, an amalgamation of mostly white drug offenders, DUI cases, child support cases, and those blacks and latinos who are either too old to have been part of the gang scene, or who were fortunate enough to avoid it, only to later find themselves on the other side of the drug economy with a pesky habit.

One by one each inmate is given a breakfast tray and a small carton of milk, and then each heads for a specific pre-assigned area of the tier. "Fin Ball" is the largest by numbers and thus the dominant gang on tier 1A, entitling them to two of the three picnic tables in the day room. "One Love" sits at the remaining. They fall in like a platoon gathered for mess, have a moment of prayer, and then begin to eat. The Neutrons are left to sit on the floor outside their cells. Laconically, the inmates shovel the paltry portions of food into their mouths, finishing in only a few moments. Invariably, all are left hungry.

Less than 15 minutes later, once all the inmates have finished and stacked their dirty trays by the door, Frosty calls the room to attention. The inmates are slow to muster, and voices echo loudly.

"On that noise!" Frosty yells. The room quickly quiets down and the inmates begin to pay attention. Frosty is joined on the day room floor by Joe "U.T." Owens, and another inmate calling himself "Celine." They stand behind him like hired goons, looking over the room.

Frosty begins.

"We know a lot of ya'll come in on the new last night," he says, referring to the nightly delivery of new inmates to the tiers, which generally happens between 11pm and 3am. "So listen up! We aint sayin' this shit twice."

The room is silent.

"Here's how it is on this deck," Frosty continues. "We all grown men here, so we gonna act like grown men. No stealin,' no extortin,', no fightin,' don't call nobody nigger. This here is ‘1A'. Ya'll got the best tier in the joint. We got that way cause we don't tolerate no boo-shit in here. We run this oursef, and the C.O.s leave us alone. So, we make the rules. You wanna fuck around on this deck, yo ass gonna get banked...hard. Everyone here is treated equal, everyone here gets treated like a man. If you need something, ask!"

Frosty pauses a second, then continues slower, with added emphasis. "Ya'll new muthafuckas get yo ass in the shower this mornin.' You been sittin' in them bullpens for two three days now, and yo ass stink! No exceptions! Any questions?"

Hearing none, Frosty concludes with "have a nice day." The inmates disperse and begin milling about.

The importance of at least the pretense of hygiene is important when you are in a lockdown situation with limited resources and a lot of men. The tiers are old and filthy in an almost cinematic way, and soap and other cleaning supplies are always in short supply, if not altogether nonexistent. Strict rules exist in order to maintain a semblance of decency. New men are mandated to shower, and all men are to wear plastic shower shoes at all times since the fungus on the floor rivals jungle rot from Vietnam. If you don't have soap or shower shoes, they will provide you with some until you can work a hustle and get your own.

There is one communal bathroom space adjacent to the dayroom, with a row of toilets and urinals opposite a row of sinks with polished aluminum mirrors above them, nearly opaque by now. No spitting or tooth brushing is allowed in the sinks as they are used for clean drinking, and to hold cold water to cool milk cartons. The last commode is strictly for sit down use, and large plastic garbage cans are stacked together next to it to provide the barest modicum of privacy. You clean up whatever mess you make...anywhere. Slack on any of the above, and expect swift and direct retribution.

Very quickly the tier becomes loud again. The television sitting high above the room bolted to a rack in the cinder block wall is quickly switched on to "B.E.T." Some inmates array themselves along the tables to play spades or dominoes or roll cigarettes. Some congregate for morning bible study with "The Reverend," a gentle and soft-spoken older man in wire frame glasses whose sole interface with those on the deck is the word of Jesus Christ; no one knows why he is in jail. Others retreat to their cells for more sleep while the new arrivals are herded into the showers, as ordered, soon to be horrified by the filth that awaits them in there, but so grateful for a few moments with some soap and hot water that for the time being, it won't matter.

Before the sun has even broken the horizon, tier 1A begins to come alive, another day in the County, unremarkable, really, from any other day. Frosty grabs a broomstick -- what the inmates affectionately call "the remote" -- and begins to change channels on the television. 1A was allowed a broomstick because it was a peaceful deck. Most other tiers, it wouldn't be such a good idea. Frosty pauses on a CBS "Special Report" which is just breaking.

"On that Noise!" he bellows. "Ya'll might want to pay attention to this shit!"

The room somewhat quiets, but its clear no one really cares. The only things that generally captures their attention are Jerry Springer, COPS, and Soul Train.

Frosty watches the coverage in silence.

...London rocked by terror attacks. At least two people have been killed and scores injured after three blasts on the Underground network and another on a double-decker bus in London. UK Prime Minister Tony Blair said it was "reasonably clear" there had been a series of terrorist attacks. He said it was "particularly barbaric" that it was timed to coincide with the G8 summit. He is returning to London. An Islamist website has posted a statement -- purportedly from al-Qaeda -- claiming it was behind the attacks...

"Shit... Ain't no mufuckin Al Qaeda," he mumbles.

The Factory

The Cook County Jail is part of the Cook County Department of Corrections, a sprawling 96-acre detention complex situated next to the Cook County Criminal Courts along California Avenue in Chicago's Lower West Side neighborhood. Most refer to it as "26th and Cal" even though the jail stretches all the way south to 32nd St, a distance of nearly a mile.

The first County jail in Chicago was built in 1871 on the now historical site of 26th Street and California Avenue scant months before the Great Chicago Fire. That building is long gone, replaced in 1929 by what is now the oldest remaining building in the complex, Division 1. This squat art-deco structure has over the years, they boast, held a fine pedigree of criminal luminaries including Al Capone and Frank Nitti, Tony "Big Tuna" Accardo, gang leaders Larry Hoover, Jeff Fort and Willie Lloyd, and serial killers Richard Speck and John Wayne Gacy.

Between 1929 and 1995 the jail complex was expanded into eleven separate divisions that range from minimum security to super-max. Cook County is the largest single-site pre-trial detention facility in the United States (Los Angeles has a bigger overall county jail, but it is split into two separate facilities). CCDOC employs more than 3,000 correctional officers and support staff and admits over 100,000 detainees a year, more than twice that of the entire Illinois penitentiary system. The reported average daily inmate population is around 10,000. The real figure, however, is quite likely higher since, due to overcrowding, it is a regular practice to put a third man in a two-man cell, sleeping on the floor.

It is also one of the most controversial correctional facilities in the nation, referred to by inmate and officer alike as the "Crook County Department of Corruptions."

In recent years the jail has come under fire for overcrowding, violence, and, naturally, corruption. There have been all manner of federal and Grand Jury investigations, and plaintiff lawsuits, into excessive beatings and inmate deaths at the hands of correctional officers. And if they didn't already have enough bad PR to defuse, between 2005 and 2006 there were a series of high profile escapes.

In June of 2005 an inmate named Randy Rencher walked right out the front door wearing a correctional officer's uniform and proceeded to rob a series of Chicago banks, sparking a nationwide manhunt featured on America's Most Wanted. On February 10th of 2006, Warren Mathis became the first inmate to escape from the new Division 11 "Super Max" unit by hiding in a laundry truck. Two days later, six inmates were allowed to escape in what the Chicago Sun-Times called "a plan to give a political advantage to a former jail supervisor [Thomas Dart] running for sheriff" by making then-Sheriff Michael Sheehan look incompetent. It worked. Rather than face defeat, Sheehan, who had been Sheriff for sixteen years, retired, making way for Dart (a Chicago Democrat) who took over in December of 2006.

Welcome to Chicago.

Anyone who has had the misfortune of being behind its walls knows all too well about the violence, corruption and squalor that characterizes this institution. Simply put, Cook County Jail is a harrowing, unforgettable experience for anyone. It is so awful that for many of its detainees a quick guilty plea and a trip to the penitentiary, even for twice as long, is preferable to staying in the County. It is the proverbial lesser of two evils.

Or at least that was how I saw it when I was arrested in March of 2005 for possession of fourteen capsules of MDMA and was facing one year in prison.

To be fair, this was my third time in County. My first stay was for a month in December of 1998 when I was busted for the second of three drug related convictions I have on my record. The first two convictions came in the late 1990s, the result of nearly a decade spent in high-intensity guerrilla warfare against a cocaine addiction while in my twenties. The MDMA conviction was seven years (and really, a whole lifetime) later, a week after my thirty-fifth birthday.

I had just returned to Chicago after spending most of the previous year on the road writing for Newtopia, an online magazine I published at the time, and organizing for the Green Party and other related factions of the progressive-to-radical anti-war and green movements. I was back in town to face a court case I had that stemmed from an assault by tactical officers (TAC squad) of the 23rd District of the Chicago Police Department, Addison Street station one year before in April of 2004. I was illegally stopped and searched, and ultimately beaten and arrested on false charges, by four plain clothes police officers who discovered I was connected to a local peace and justice group that was involved in fighting police corruption.

The charges against me were dismissed and the judge who heard the case acknowledged wrong doing by the police. From that moment forth I can only assume that, fearing a civil rights case which I fully intended to file, these cops were committed to stopping me somehow. I was watched, I was followed, and a few weeks later I was rousted, and ultimately arrested for having the ecstasy by TAC squad officers from the same precinct house, one of whom I later identified as one of the four present the night of my assault.

It's important for me to take a moment here and explain that I was not using ecstasy recreationally. I wasn't a "raver" and I didn't merely transfer an addiction from one substance to another. I was reintroduced to MDMA in a therapeutic context in 2004. Prior to that it had been since the early 90's that I had even taken a single dose.

Friends from my community in Chicago, who were fellow drug war activists, were also intimately connected to the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, who had done pioneering work on MDMA therapy for those suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Many of these friends, as well as psychotherapeutic professionals I knew at the time, helped me to see that I was suffering from a form of PTSD brought on by the effects of violent experiences in my past and my prolonged addiction to cocaine, and that some form of MDMA therapy might help me.

Although at the time there were no clinical studies available in the US, much less a regulated program of treatment (in other words, because I couldn't do it legally) I had enough information and guidance to feel comfortable, and risk, experimenting on my own. Although later on in the book I will go into detail about the specifics of the therapeutic work I did that began with MDMA and other substances and then led to more traditional therapies, it's important to understand that this was the reason I was in possession of the MDMA at the time of my third arrest. It was a risk I was willing to take, and I do not regret it. The experiences chronicled in this book led to a complete transformation of consciousness which would over the next four years completely transform every aspect of my life.

I understand I broke the law, and so, many will see my punishment as deserved. The case I will make is that the laws surrounding drug use are unjust, particularly for those drugs with the capacity to heal, the punishment does not fit the crime, and in fact does far worse damage, and that my experiences reveal that the system itself is broken, a self-perpetuating machine of dysfunction that remains in place for reasons wholly separate than either drug enforcement or criminal justice. In many ways, it is about cognitive liberty above all -- the freedom to learn, heal, and grow however you wish by whatever methods you choose, the freedom to experience life in the manner of your choosing.

After I was arrested I would spend three months dealing with my case until it became clear to me and my lawyer that with a third conviction and a precinct house full of over-zealous cops hell-bent on covering their collective asses, I could not avoid prison time.

This was a particularly bitter pill to swallow for two reasons. The first and most galling was that I was no longer a drug addict. I took great pride in that. Breaking that addiction was the hardest thing I had ever done, and I was long past engaging in any of the at-risk activities that led to my first two arrests and convictions. The second reason was that the substances I was being punished for having in my possession had helped me immeasurably, in a very short time, begin to face demons that had been consuming me my whole life. I considered them my friends.

What was all the more ironic was that as I was recovering, probably as a direct result, I spent a few years investigating the drug war in great detail and had begun writing about it. I also got involved in activism trying to reform drug laws through various lobby efforts. I had been building a respectable body of work, and in that work I had been steady about one thing: our national drug policy was absurd and had no impact on either drug use or supply. It was economics, moral policing, and social control, and it disproportionately punished the poor. I constantly argued that warehousing drug users as prisoners was a waste of public resources that were better spent on our communities, and that there were better things drug users could be made to do. The irony was not lost on me that I was now living proof of my own theories.

Thus I returned to Cook County Jail on July 1, 2005, after accepting a guilty plea and taking a two year sentence (one year in the penitentiary and one year of parole) let's be clear...for having a few pills in my pocket that made me want to give everyone I knew a hug. But that's an argument for later on.

I had to surrender myself in the courtroom and be led away through that mysterious back door behind the judge that the public never gets to see. As I stepped through it, I turned and smiled goodbye to my friends gathered in the courtroom for support, and I didn't take a normal breath for months. As the door closed behind me I literally had to put on another persona, one which I would keep until they let me out and I could go back to being myself, which would take far longer than I ever imagined. In many respects, I never did.

I entered what is known as "Dead Time," or the time a convict spends in the county jail awaiting shipment to the penitentiary system, which, no matter how long it takes, does not count towards the overall sentence. It was also literally dead time in my life, vita interruptus, weeks and months taken from me. Though I harmed no one and nothing, I was now part of an exile nation of American radicals, convicts and detainees millions strong, where I would burn off my "sins" in service to the State, in what is commonly known as the "Prison-Industrial Complex."

The Gateway to the Underworld

The first challenge of this yearlong odyssey I had before me was to get through Intake & Processing, a long and exhaustive ordeal that tests the very limits of your patience and mettle. It is where you quickly have got to adapt to a new reality in order to survive. Even if you've been through it a dozen times -- which is not uncommon, since the recidivism rate is disproportionately high -- the process is traumatic, and leaves you wasted for days. For many, this will be the first time they will have their basic freedoms rescinded and experience the methodical cruelty and dehumanization of this kind of "factory corrections," or the production, management, and warehousing of large numbers of offenders.

Every day paddy wagons from police precincts all across this nation's second most populous county converge on the jail's receiving dock to offload their shackled human cargo into a dark and dingy chute which leads into the bowels of the jail complex.

Because of this charge, and the three months in between while my court case was in limbo, I had to go through jail intake twice, once when I was arrested in March of 2005, and again in July when I went back into the system after being on electronic monitoring, or "house arrest," a program to combat jail overcrowding. The initial arrest was on Good Friday, and I spent Saturday in the police lockup at Belmont and Western before being transferred to Cook County on Easter Sunday. I did not see a bond judge at the Belmont & Western precinct, which had been my experience seven and eight years before respectively. Before taking the lot of us to Intake and Processing, we were herded into a series of three dark and filthy, horribly overcrowded holding pens to await a bond hearing via closed circuit TV.

In "video bond court," detainees appear one at a time in a small room with a camera mounted on the wall above them. Meanwhile, many floors above ground and down the street in the Criminal Courts complex a bond judge, state's attorney, and public defender discuss their fate.

The experience is uniquely totalitarian in the purest Orwellian sense, a Kakfa nightmare where the detainee, literally, has no ability to speak for himself, and it is doubtful given the sheer volume of faces passing on and off the black and white screen that any of us were actually viewed as people. We were nothing more than depersonalized names and prior records next to subterranean faces distorted on an old monitor, which, from what I saw, the judge didn't even bother to look at.

Bond, if given, is determined by the category of the detainee's crime (felony or misdemeanor) the relative degree of the crime (Class 1-4 and X), and any prior criminal history. Because of my prior record, I was given a $40,000 "D-Bond," which would require me to post 10%, or $4000, in order to gain bail. It might as well have been $4 million; I had less than $200 to my name.

A very few lucky souls with misdemeanors or first-time petty nonviolent felonies (like a Class 4 nonviolent possession of a controlled substance, my crime) will be released on an "I" bond to their own recognizance. Most will be remanded to the custody of CCDOC until they can post bail or their case is resolved one way or another.

It is important to remember, as you read what unfolds ahead, that none of us had been convicted of anything yet, and some of those held in these conditions were in fact innocent, but simply could not post bail.

Those charged with nonviolent offenses become immediately eligible for the EMU (Electronic Monitoring Unit) but still must spend a day or more going through Intake & Processing and anywhere from a couple days to a few weeks on a jail tier before an opening takes place and they come around to collect you. Luckily, I did qualify for EMU. Nonviolence does get you somewhere.

Each day around 300 detainees are processed in a large room deep underground beneath Division 5. Age and wear are evident. The room looks as if it has not been cleaned since it opened in the mid ‘70s, and the stench of smoke, urine, and vomit is at times overpowering. Along the perimeter of the room are a series of bullpens into which detainees are stuffed like chickens in a factory farm, to be shuffled and reshuffled from one to the other and back again in no discernible pattern while moving through the various stages of admission.

Only one bullpen has toilet facilities, and they are so befouled that inmates are made sick simply by looking at them. Yet, for the disproportionately large number of detainees who are addicted to heroin or alcohol, it is the only place for them when their bodies turn on them violently. This becomes the background music of the world's most cramped waiting room.

Detainees are led from the first bullpen to be fingerprinted and issued an 11-digit ID number based on the current year and overall number of entry (my number was 05-23995, meaning I was the 23,995th person processed in 2005). Photo ID cards are issued, which are kept by correctional officers at the individual tiers or living units within each respective division. A series of "interviews" with staff personnel determines basic personal information: name, address, employment, next of kin, and most importantly, prior record and gang affiliation. These, weighed against the detainee's current charge, will be used in creating a security classification of "minimum," "medium" or "maximum" determining where you will be housed. Without explanation, I was given a "medium" security designation, which I later discovered is given to virtually all nonviolent drug crimes.

All personal property, except for wedding rings, is turned in and any cash money is collected and put on account. Detainees pray that they will see either again. Many won't.

A very precursory medical history is given. Blood is drawn for TB and syphilis, a chest x-ray is taken, and -- dreaded last -- a visit to the "dick doctor" for a quick and painful cotton swab down the urethra for a STD screen. You really can't fathom what it feels like to have a nine-inch Q-tip shoved into your urinary canal. The terror it strikes into a man waiting an hour to have the procedure? I had it done the first time I was in County, in 1998, and it sucked more than you can ever possibly imagine, unless, of course, you've had a catheter inserted while fully conscious, in which case, my brother!

There was one ray of hope that day. Word rippled through the line that a class action lawsuit had ended the reign of the dick doctor. Every man down that line shivering in his underwear heaved a deep, near-hysterical sigh of relief (as, I'm sure, did every male reading this). Some court had finally come to the rescue, a distinctly unfamiliar experience to most of these men, whose only association with the court system is generally punitive. The system can work, every once in a (deep cobalt, near black) blue moon. Unfortunately, it takes something as severe as a traumatized urethra to get anyone's attention.

In between each of these stages detainees are left standing for hours in the bullpens. Naturally, it is unreasonable to expect anyone to stand that long, so eventually people begin to collapse onto the filthy floor, and onto the few benches along the wall, chests tucked to knees, unable to move. Regularly, correctional officers will come by and scream into the bullpens about the noise, or people sitting down. They make threats, make everyone stand up, leave, and the process begins all over. It becomes this absurd pantomime, a futile back and forth of authority and rebellion, insurgency and counterinsurgency, stuck in an infinite feedback loop.

Contempt and disgust pours from the faces of the CO's and you wonder what makes them so hate-filled, before you have to remind yourself that some pretty nasty individuals have come through here over the years, and after a while, it must get to everyone. Still, you wonder why they even bothered taking the job in the first place. What did they expect?

This ritualized abuse and debasement would only get worse as I went into the prison system, a systematic brutalization of the basic human rights and dignity that I faced with every turn. You couldn't even ask a simple, innocent question without running the risk of getting your skull cracked. They simply didn't care; you were like livestock to them, filthy, stupid animals that deserved nothing. It must have been what they had to think to even live with themselves. Deep inside, few humans want to be that cruel. Or do they?

Over time, stuck in the bullpens waiting, the men become more and more filthy and the stench in the room transmogrifies into a dull rancid taste that coats the back of your throat. That nasty taste still haunts my memories, surfacing in my dreams, like a sickness lingering.

A transsexual prostitute arrives with a large shipment of women detainees(1) from one of the West Side precincts, and the "White Shirts" -- sergeants and lieutenants -- decide he/she has to be isolated, so the men lose the use of one whole bullpen. The net result is that the tranny becomes the object of vicious, relentless abuse by both the COs and the detainees, and the remaining bullpens became so overcrowded they resemble passenger trains in India ferrying peasants to the Ganges.

Many hours into their ordeal, and perhaps days since their original arrest, detainees are ordered into a final bullpen so that they may attempt to make their "one phone call." However, despite popular misconceptions that everyone is entitled to a call (among other things, like Miranda rights, and the right to see an attorney, which are also mostly media fabrications) there is only a limited amount of time for 300 odd people to make their calls, and everyone has to share what during my experience was five working phones out of eight total.

These phones are a hell unto themselves. They are not coin pay phones, and there is no operator assistance or 800-collect numbers. They do not call cell phones, and you cannot leave a message. They are specifically designed for use in correctional institutions. They have a singular function: automated, direct-dial, direct bill calling, which means you can only reach a number on an established land-line that does not have collect call blocking, or in the case of many recidivists' families, correctional call blocking. You punch in the number you want to reach, it records your name and puts you on hold while it makes the call for you.

When the call arrives it plays a pre-recorded message that says, You have a collect call from [your recorded name], an inmate at the Cook County Jail. If you wish to accept this call, please press "1" now. Charges are $2.80 plus $1.00 for each additional minute.

You pray someone accepts the call.

Because of this, many of the detainees reach no one, and spend their time begging for a "three-way" call from one of the fortunate few who did successfully reach someone in the outside world.

This dearth of phone communication is somewhat alleviated once inmates are safely tucked away in their housing units. Once there they have regular access to phones. Correctional telephone services are a multibillion dollar a year industry, and County inmates sometimes spend up to a year or more awaiting resolution of their cases. The phone providers are fully aware that they are the detainee's only link to the outside world. Inmates are totally dependent on them to communicate with family, lawyers, and loved ones, and it all adds up. Of course, it's not the detainees that are paying the astronomical phone bills, their families are, in effect adding another level to their punishment and creating an even further imposition of hardship, as the vast majority of detainees and their families are poor.

Perhaps the most gruesome and dehumanizing aspect of the intake process is the mandatory strip search. I lived through three different strip searches in the basement of County over nearly an eight-year period and they were all the same. In groups of roughly 75-100, detainees are led into a long, narrow underground tunnel outside Intake & Processing in which a group of very large white correctional officers with fat, beefy biceps, either close cropped or bald, stand around wearing latex gloves and looking as if they would rather be exhuming the dead than in that tunnel with all of us. We are lined up shoulder to shoulder along the wall. At our feet is a yellow line.

"Listen up, motherfuckers!" one of the thick-necks shouts. "Pay attention, do exactly as I say, and this will go smoothly! Do not talk, do not move unless told to! God help you if we see you moving or talking! You do not want to fuck with us today!" As if today might magically be different from any other day.

We are instructed to remove one article of clothing at a time. Pants are to be held upside-down by the cuffs and gently shaken. Shoes are to be turned upside down and banged together. We are told that because we may "have bugs and god knows what else living on us and in our clothes," if we shake our clothing out horizontally in their direction, we will not only lose that article of clothing permanently, we will also "regret it." They make this point very clear, and no one shakes their clothes.

Down the line someone suddenly vomits across the smooth concrete tunnel floor. Before half of us are aware that he had puked, he is forcibly dropped to the ground by one of the C.O.s, who shoves his face in it, and orders him to wipe it up with his own shirt. When he heaves as if to vomit again, the C.O. kicks the guy and tells him that he'll have to clean it up with his hands. The tunnel fills with the stench, and another detainee breaks rank and stumbles to a nearby garbage can. Instantly another C.O. is in his face screaming at him, "You puke in that can, you're cleaning it out with your bare hands!" He is forced back into line.

The process continues. Eventually, we stand naked, our clothes in a pile at our feet, the stink of alcohol-puke drifting down the tunnel. We are told to turn and face the wall, then to bend over and grab our ankles. On the count of three, all are instructed to cough loudly. This is ostensibly to check and see if we have drugs or other contraband shoved up our ass, but the method they employ is so easily faked that you can't help but feel that its primary purpose is to degrade us. The percussive thud of the collective cough echoes off the concrete. Standing back up, we remain facing the wall, foreheads pressed against the concrete, arms above our head, palms facing outward as instructed.

"This is your last chance!" one C.O. shouts. "If you got anything on you, or in your clothes, tell us now or you'll end up catching another case!" No one is stupid enough to believe him, so the tunnel remains silent, irrespective of what anyone may or may not have on them.

The C.O.s move up and down the line picking up shoes and articles of clothing, searching through them, ripping out insoles and throwing things recklessly back down to the cold floor. Near the end of the line, mere steps from me, a large, bald headed C.O. finds a $20 bill stuffed deep inside the lining of a shoe, a common practice amongst young men in the hood who are used to being robbed. The C.O. spins the naked inmate around to face him.

"What the fuck is this?" he says, sticking the bill in the man's nose.

"Man, I forgot it was in there."

A "White Shirt" sergeant steps forward from behind the C.O. and, with latex gloves on, open-hand slaps the inmate across the face. "What the fuck did we just tell you!? You think you're slick? You think we're idiots?" The C.O. pockets the money, and shoves the inmate back against the wall. No one dares raise their head to see what is happening. No one wants to be a witness to anything like this. But everyone knows exactly what is happening. It is nothing new.

When they are finished searching the clothing we are given exactly fifteen seconds to get fully dressed. If we do not get everything on in fifteen seconds, we are told, we will have to leave whatever is left on the floor and it will be thrown out. Rarely do you see humans so exhausted move so fast.

One at a time, by security designation -- minimum, medium, maximum, and super max -- we step forward, turn left, and are marched out in single file lines to another row of impossibly cramped holding cells. Here we will eventually be fed a borderline-legal bologna sandwich and maybe a little 6oz plastic bottle of some artificial juice drink while we await transfer to our living units, which can take anywhere from three to four hours.

These bullpens are even smaller than the ones in Intake, and none of us can move, stand up, stretch our legs, or use the bathroom. The benches are filled and men sit pressed together. Some are lying on the floor under the benches, making every square foot of open space occupied. It's so hot you can't breathe, and you never imagined people could smell so god damn bad.

Now, hunger begins to set in, which is particularly egregious to vegetarians like I was at the time, who have no option but to eat bread soaked with bologna slime, or go hungry. I mean, I could always make an argument to eat meat, but we are talking about no meat born of nature here. We are talking about an unholy creation of unspeakable evil, cast off from the rest of humanity down to us subterranean scavengers. After seven years of not eating meat, I feared it would kill me. So I went hungry.

When the time comes, hours later, we are dislodged from the holding cell and taken to our assigned divisions through an elaborate series of underground tunnels. This generally takes place very late at night or early in the morning.

Before being brought up to the various dorms and tiers we must make our last stop, in the clothing room, to turn in our street clothes and get issued a grey plastic property box about the size of a small trunk, a brown CCDOC uniform, blanket, mattress, and, if lucky, a "hygiene pack" which can include any combination of toilet paper, soap, towel, toothbrush, toothpaste, and deodorant, never all at once, rarely more than two or three items at a time. It will take an hour to distribute all the personal effects and store all the clothing. In that time, inmates make informal bets about which of their clothing will make it back to them. Anything leather is considered a goner.

One by one, property boxes held before us, mattresses folded on top, we begin a long climb up a narrow concrete stairwell three flights until we reach the living units, or "tiers."

Each tier in Division 5, and a few other Divisions built just like it around the same time, is made up of a large square room with yellow cinderblock walls and concrete floors, and is split into three separate levels. Cells line one half of the room on decks just above and below the day room which is on floor level. 22 cells per tier, 11 on the upper deck and 11 on the lower, making the population count officially 44, and with three-man occupancy, sometimes as high as 60.

The "day room" is a common area with high ceilings pockmarked by high-intensity halogen lights and a few old surveillance cameras. Three stainless steel picnic tables are bolted to the main floor. A bank of three pay phones are in the far corner. The third wall has a common bathroom and a common shower. The exit door, and the security bubble, occupy the last wall.

By the time I actually step foot in tier 1A with six other guys it's around 11:30pm. After ten o'clock on any given night the tier is generally on lockdown and all inmates are required to be in their cells. A few members of "Fin Ball" remain outside in the day room to sweep the floors and keep the barter economy alive by ferrying goods between cells.

Through "chuckholes" -- narrow vertical monitoring slots cut into the center of the steel cell doors -- inmates "chirp" to each other, calling out across the tier, begging cigarettes, trading commissary food, corn pone crime novels, raggedy porn mags, whatever it takes to pass the time and feed the persistent hunger in your gut...or soul.

As we walk across the day room, calls of "On the New!" emanate from various chuckholes. As we pass by their cells, the other inmates scope us out, scanning for friendly or familiar faces.

"Who yo wit little nigga?" someone asks a young black kid standing next to me. Who you wit is the first thing anyone asks you, because your gang affiliation, or lack thereof, is everything. This impromptu recon work is essential for all to become aware of their place on the deck. With few words, the natures of relationships are established, and a hierarchy is enforced.

"Wit dem Stones," comes the kids' reply, referring to the Blackstone Rangers gang. His hair stands a foot high after being forced by jail personnel to take out his braids. Officially, they tell you, braids are removed because they are "gang symbols," but they don't only make gang members debraid. They make all black men do it. Ask any brother and he'll tell you it's to humiliate them, to make them look like dirty pick-a-ninnies when they are hauled cuffed and shackled in DOC scrubs out in front of the Court. Lookin' like that, they say, they're guilty before anyone can utter a word in their defense.

"Who got dis?" big hair asks, motioning his head to indicate that he is curious which gang runs this particular tier.

"Fin Ball. They got chou. These niggaz straight Vice Lords."

(Loose Translation: "This tier is under the control of the People Nation, mostly guys from the Vice Lords. You are safe here, you have back up.")

"Ah-aight, den. You ride?" ("Cool. Are you one of us?")

"G.D., yo." ("No. I am with the Gangster Disciples")

Realizing that he now can do whatever he wants -- within the rules of his crew -- and realizing he has to establish himself now on the tier, from this point on in the conversation, the youngster engages in mostly unnecessary bravado.

"You straight?" ("You got an issue with us being in charge?")

"Naw. This mufucka straight." ("This tier is peaceful and ordered, so yes, I am fine with it and we shouldn't have a problem.")

The youngster eyeballs the cat in his cell as he passes out of view, then looks over at me.

"Sup wit chou, white boy?" the kid says, antagonistically. I just ignore him. I am so thoroughly exhausted by this time that I can barely stand. All I want to do is sleep. The unit C.O. opens the various cells by hand and directs us inside, two or three at a time. My cell is on the lower deck, just under the stairs that lead to the upper deck. However, sleep is a long way off.

Luckily, the cell I'm assigned to was just turned over and stands empty, so there is no need to establish myself as the new guy with my cellmates. And since the three of us just spent all day and night together in processing, there is an instant air of levity and relief once the door lock slams home and we are left to our own limited devices. It is a strange and powerful sense of relief; you know that for the next five or six hours no one will bother you, and you can sleep.

I was lucky that last time. The two other times I had been in County were significantly harder since I was stuck in cells occupied by gang members and was forced to be the man on the floor. It meant I never had anything close to privacy, and I had to do all the cleaning, and they took what they wanted from my food tray. You don't even think about telling them "no."

This time around my cellmates were an old Irish guy named Mike who had this red bulbous pockmarked nose that made him look like JP Morgan, and this twenty-five year old white kid from Idaho. Old Mike got busted while in his car buying heroin for his dope sick girlfriend, who couldn't leave the bathroom. The kid had just moved to Chicago with his 20-year-old girlfriend to work in commercial production, and got locked up for punching her in the face after gettin' lit on whiskey.

We unroll our filthy, stained foam mattresses on our respective bunks -- me on top, Mike on the lower, the kid on the floor -- and we each stretch a sheet across them. Each man urinates once in succession in the stainless steel toilet that sits next to the two bunks then drinks some warm, slimy water from a tepid bubbler in the sink. We crawl in to bed and listen to the kid go on and on about how sorry he is for hitting his girlfriend, that he had never done it before, that he was drunk. He tells us that she was already headed back to Idaho, and he asks us how he might get her back. Neither Mike nor I say much. The kid begins to cry.

"Listen," I tell him. "It's cool that you're doing that now, in here, but don't let those other cats out there see you do that."

The kid, looking perhaps a bit too terrified, quickly wipes the tears from his face.

"What's the deal? Are they gonna try and rape me?"

"I really don't think so," I told him. You could tell he had never been in jail before. "That kind of shit doesn't go on much in the County. But these youngbloods out here, they prey on weakness. So, if you wanna eat, and you wanna be left alone, you can't show weakness. Just be cool. You'll be out of here tomorrow. Get some sleep."

"Good idea," Mike grunts. "Let's start with the light?"

The kid gets up and turns off the light. From another cell down the way on the lower deck comes another voice chirping out of a chuckhole.

"U.T.?"

"Yo!"

"On the reach!"

Two arms emerge from the chuckholes of two adjacent cell doors like elephant trunks snaking in and out of zoo cages, stretching out plaintively towards each other, groping blindly. One hand is empty; the other holds a few "rolls." They eventually connect and pass the cigarettes from one to the other, and the arms withdraw back into the cells.

Slowly over the course of the next half hour or so the deck quiets down as most inmates finally go to sleep. The television high upon the wall is turned to a Jerry Springer rerun, and the volume comes way down. Through the cinder block wall in the adjacent cell, U.T. can be heard preaching to his two new cellies about how a division between light and dark skinned blacks was created by white slave owners to create a persistent atmosphere of divide and rule.

...thaz how they got dem Bougies, dem high yellow muthafuckas livin' in Massah's house who think that they better than dem field niggers, who is dark as night. And the field niggers, all they thinkin' ‘bout is how come "Massah" like dem Bougies more? Its cuse dey be part "Massah," cause he be fuckin field niggers every damn night, and dey start havin babies.... So, right, they end up hatin' on their brother, and not on the man who is enslaving them, because the light-skinned brother reflects the image of the Massah. And that shit still goan on today. Young boys be killin' deyselfs in the ‘hood, and black folk be killin' other black folk even back in' Africa.... You remember Rwanda...that was the same shit. When the white man came to Africa, he favored one tribe over another, so the other tribe spent all dey time hatin' on the favorite tribe...

Back in our cell the kid asks me, "Why are you in here?"

"I'm on my way to the penitentiary. I got a year for some ecstasy."

"Jesus. How much, like a pound?"

"I think the final count was eleven capsules. A few disappeared in the booking process."

"You gotta be shittin' me?"

"Wish I was."

That's so lame! How do you deal with that?"

"What choice do I have?"

"Dude, I'd freak."

"Well, be grateful it's not you."

I pause, then roll over and look down at him on the floor.

"But if you don't stop beating up women, it will probably be you."

"Dude, come on, I don't beat women."

I didn't want to argue with him. "Anyway, it should be interesting."

"Man, I'd be so pissed."

"Find me someone who wouldn't be."

Mike begins to snore, a vicious, snorting apneac rumble, quite possibly the loudest, most phlegmy sound I have ever heard. My assessment is confirmed when a voice from above on the upper deck breaks the silence.

"Man, somebody shoot that fool!"

Sleep never really comes. I fade in and out of a sort of semi-sleep, as if I keep practicing the opening bow to a waltz, but never actually begin the dance. My mind stumbles around in circles. I think of my dog, but it makes me too sad. Of all the hard things I had to endure the previous three months, I never thought saying goodbye to my dog would be the toughest. It nearly broke me. Go figure.

There's your hardened convict for ya.

A Correctional Cosmology

There is a delicate balance to life on a jail tier. There is a class strata, an economy, and an ecosystem. Divide and Rule is the way order is kept. When inmates have to police themselves, and watch their backs, the dynamic takes on a very different character, and a certain stasis is reached. There is generally just the right mix of gangster and neutron to keep a strange and unexpected harmony. But underlying it all is the understanding that, although County is at times the very likeness of despair, no one wants to make their stay there any worse than it has to be by being sent to solitary or by having your skull cracked by overzealous C.O.s armed with clubs and really bad attitudes. When things go wrong in County, people get hurt.

During my stay in 1998, gang members on my tier were suspected of selling various forms of contraband, so they sent in the SORT team (Special Operations Response Team), otherwise known as the "goon squad." We were all stripped naked and zip-cuffed behind our backs and made to kneel on the floor of the day room as every cell was tossed. When they located guilty parties, they beat the shit out of them right in front of us, and then hauled them off to segregation to face more charges. This type of abuse was rampant in County. Only two months later, in February of 1999, SORT officers viciously beat and turned attack dogs on 400 inmates in Division 9, and then engaged in an elaborate cover-up. (2)

To maintain order and create routine every jail division has to follow a regimented schedule. In 1A we were woken up for breakfast around 4:30am and then were required to stay out of our cells in the day room for a couple hours until around 6:30am. Cells open at 6:30, and those wanting to go back to sleep can until lunch, which is around 10:00 or 11:00am.

It is up to the discretion of the unit C.O., but depending on the tier, inmates can either come out of their cells, or remain inside during lunch, but not both. If they choose to remain inside they remain locked in until 4:30pm when dinner is slated to arrive. Inmates must be out of their cells for the evening hours, which end at 9:30pm. This staggering of inside/outside is meant to keep the inmates moving around and visible, thus reducing the various malfeasances that can occur out of sight when groups of people congregate in a jail cell or two. It is also a liability precaution meant to help assuage suicide attempts.

I preferred whenever I could to be alone in my cell reading. It occupied my mind with something other than prison bullshit and it gave me some peace, so I would try to remain in my cell during those midday hours. I would stuff my chuckhole with toilet paper rolls and slip a milk carton over the light bulb, and I would be in my own little private space for a precious while.

Inmates were no longer permitted to go to the County library in 2005 (actually, I was told library visits were done by written request only, and they never granted any requests) so the only books available on the tier were a few smuggled FBI crime novels that were so awful they made me sad (well, that and the fact that many of them had been be

Sometimes reading is all you have to keep you from losing it. At least that's what it did for me. Over the next few months while I burned off time in the penitentiary I would read probably three dozen books, some of which I was shocked to find in a prison library, books I had wanted to read my whole life but (savor the irony) never would have had the time for in the outside world like I did while locked up. Strange blessing, in a manner of speaking.

Frosty and I are watching TV. At one point he leans in close to me and says, "You know these mufuckas think you a cop?" I look over at him and he smiles mischievously, signaling to me that he does not share that opinion.

"Story of my life," I tell him, and wasn't lying. I had this problem when I used to buy drugs on the street. It's a whole different world when you have to navigate housing projects and ghetto blocks, places where often the only white faces ever seen are cops. Most of the major cities are segregated this way. As the white customer, I would slip into a virtual shark tank populated by cops, gangs, hypes and rogue scammers, and I would have to get in and out before I was noticed by any of the above. If you think about white suburbia and their predilection to view every black man passing through their community as a criminal, it stands to reason that on the reverse end every white man coming through the hood is either a cop, customer, or mark. They were certainly conditioned to see things this way.

But because I looked like I did -- which is to say at the time I went into County I was clean shaven with a buzz cut at a healthy and robust 200 pounds and not strung out -- they decided I had to be a cop...because I looked healthy. This particular wariness and paranoia towards me, I discovered, I had brought upon myself, and then was naïve enough to think I could overcome it.

"Am I in any danger?" I ask him.

Frosty laughs. "Not now you aint. Few months back, sheeeit. This place was buck wild. GD punks had this, young boys, and they were downright cruel."

He points over at a young Polish kid who spoke no English playing chess with "Sensei."

"They made that man wash their clothes, their goddamn shit shorts. They were straight up looters, they took everybody's shit. Then me and U.T. and Celine and some of them Vice Lords came on the deck, and we finally had to go with ‘em. C.O.s let us take care of it, I ended up breakin' their chief's jaw, and when it was over, they hauled all them muthafuckas out and put them next door. Now, it's a damn circus over there every day, and they never bother us in here."

Frosty pats me on the back. "But you came close." He laughs, and walks away.

Allow me to explain.

Asking a lot of questions is not advisable behavior while locked up. Period. Some people know this instinctively, and just keep to themselves, or if interacting, make small talk. The gang members are like that. They don't talk to anyone but themselves, and they are automatically suspicious of every one and every thing. Some people learn quickly not to be nosey, others slowly, and a few the hard way. And of course some just never learn. Those people get ignored or worse. I came perilously close to being one of them.

No matter what my excuse was, whether true or untrue, I discovered there is nothing cool about writing down shit someone else is saying while you're locked up. It's simply a bad idea, and one I wish I had considered more before I did. It was bad enough most of them had never met a journalist, but as far as they were concerned, a white guy with pen and paper was either a cop or a snitch.

They were mildly impressed with me in the beginning because I got busted with what they saw as a glamour drug, one that they themselves would consent to take. And at the time, MDMA was becoming popular in their culture and they showed interest in exploring the intricacies of supply and demand. I felt like they were testing me. If I wasn't a cop, they deduced, then I must have been busted for dealing MDMA and was asking questions because I was trying to get info on other people in order to get a deal with the State's Attorney. They asked me what I did "out in the world" and I told them I was a journalist, a writer, and that I was going to write about my experience in prison. They didn't get it, or trust it. So I tried to explain to them the irony of being a drug war activist incarcerated on a drug charge, but most of these guys were short on irony and they didn't know or care what an activist was. They just wanted to know who or what the fuck I was, and whether I posed them any threat.

What confounded them was that I knew a lot about what their lives were like on the street, and about black history, and I had my own ideas on the role of race and class in the drug war and the prison economy and I tried to talk with them about it. I am willing to guess this was shit they did not usually hear other white people saying, and I spoke about it with frankness and directness, something they were also not accustomed to. I made a conscious decision to try to bridge the divisions between us as best as I could by trying to let them know that despite how really out of place I sounded and appeared, I understood them better than they thought, and had been "down low" too, just like them. Shit, we were all headed to the penitentiary, so how much better or different could I be?

They didn't go for that one bit. And it was because it was all too apparent that the big equalizer in jail is education. Most of the men around me never finished high school. I was the only college graduate on the tier.

Education is valuable when you are locked up because if you are smart and can perform a function for those who run or influence or protect things, you become valuable. But you also stand out like the lunatic wearing the sandwich board. Not only are most of your ideas foreign to them, but your education belies the real animosity and source of distrust, which is in the class difference. The white and educated are not trusted because they are the "Haves."

Of course, just because they were largely uneducated did not in any way mean that they were stupid. They may have been living in a different reality, but they were not unaware of their circumstances. Say what you will about the moral failings of drug dealing, these kids understood market economics better than most of us. It's quite simple for them, this is a business. They have no other opportunities. They don't care if drug dealing is morally ambiguous, nor did they seem to care that they were sitting in a jail cell for it at the moment. Dealing was better than virtually all their alternatives, and jail was a necessary, and somewhat predictable, rite of passage for anyone in the game.

But more than morality, these cats understood human nature, human need and human suffering. Contrary to myth, gang youth don't take the drugs they sell, which is usually crack or heroin. They do so under penalty of death from their own ranks. But it's not the death sentence that keeps them from turning down that path, it's seeing firsthand the daily effects of their trade, seeing people slowly decay, seeing them beg and degrade themselves for hit after hit, seeing what they will let other people do to them in order to get...just...one...more...hit. Most of them had lived through the devastation that crack wrought on a whole generation of their people, their mothers and fathers and cousins and uncles. Because of that, most have nothing but contempt for their customers. The Office of National Drug Control Policy could not have written a better prevention campaign themselves.

Frosty would later advise me to "take notes in my head" after the two gangs held an impromptu meeting to discuss me. I saw the meeting happening, but had no idea it was about me until Frosty came into my cell and told me. Although they did not reach a consensus, they decided that whatever I was, they were going to stay far away from me. None of them would talk to me after that, and from that point on, the tone on the tier changed towards me markedly.

If I were anyone else, this would be a blessing. Because no one wanted to risk the chance that I was a cop or informant, everyone left me alone. For me, as a writer needing material, as an investigative journalist, as an activist seeking understanding, it was a total hassle. I wasn't afraid of them, I was curious about them, about who they were as people, not as gangland mythology, and it pissed me off that I was lumped in the same category as the shithead cops who had put me in this position. Again, luscious irony...choke it down.

Talking to someone like "U.T.," however, proved all-too easy. It was clear already how much he loved to preach. I suppose what made him interesting to me was the indifferent matter-of-factness with which he spoke, as if he no longer was concerned with what was going to happen to him, or what people thought of him. He exuded total acceptance of his situation, as if he no longer expected anything.

He was 45. Ten years earlier his life changed forever when found his mother dead in her home. She had been dead for over two days, and no one had noticed. Since he was very close to his mother, he was unable to forgive himself for not calling her or stopping by, and it shook him to the core.

"She was my best friend, the only person who ever believed in me."

He abandoned a good life with a wife, kids and a job working as a security guard, and he hit the streets with whatever money his mother had left him. He stopped caring about anything, intent on smoking cocaine until his heart exploded. Invariably, this lifestyle led to many busts, and he began his own personal 10-year square dance with the Illinois Department of Corrections, dosey-doeing his way in and out of prison on drug related charges.

"Politicians are no different than mobsters," he says, "They say they want to stop drugs, but they are the ones letting the drugs into the country."

Before him is a pile of loose tobacco and a pack of papers. His long tapered thumbnails furiously produce hand-rolled cigarettes one after the other, a service he provides for others on the deck in order to get free cigarettes as a commission. His ability to roll is quite a thing to behold, so everyone comes to him.

He lets his hands pause for a moment, and he looks at me, suddenly bearing deep and pronounced gravitas.

"What you need to think about is these here young boys, what this country gonna be like in twenty years. We're turning into a third world nation. Too much greed, and nobody knows shit about nothing anymore. But...life is indeed precious. Even those who don't think they amount to something have value."

He flips me a cigarette.

"God don't make no junk."

Lane arrived on the tier three days after me and took Mike's place in my cell after Mike was transferred to the Senior wing. Lane was 26, from the West Side, and worked construction. He had spent his entire life trying to stay away from gangs and out of jail. Lane's older brother had, for complicated reasons, taken the rap for a murder a cousin had committed, and got life.

It was worse for Lane because he was in for a series of DUIs, so he was pissed at himself because he had no one to blame but himself. His girlfriend and his son lived in the far western suburbs and Lane often had to drive out there late at night. That he chose to do so often after drinking all night with the guys on his crew was perhaps the ungallant part of his story. But Lane was one of the good guys, and he loved his son, so with dignity he accepted 30 days in the County.

"If this is what it takes for my shorty to grow up as far away from the West Side as humanly possible, than I'll sit," he says, smiling. "Man, every time I think of that little guy my heart gets big. He's like a little man, and he don't fear nothin.'"

Still, he rankled at the surrounding company.

"These West Side niggers...they'd leave your Momma in the street to die."

He leans his head against the metal grating that covers the "window" in our cell, his hands placed before him on the sill. He breathes a long, slow exhale.

"Man, what am I doin' in here?"

"Seconded, and passed," I mumble to myself.

Soul and "22" shared the cell on the other side of "U.T." Soul was from the same neighborhood as Lane, and the two had gone to the same high school. Soul sold drugs, but was unaffiliated, and tight lipped about how he managed to survive that way without getting clipped.

"22" was so named because he had size 22 feet. He wore white Nikes with a purple swoosh that made his feet look like two pontoons. You couldn't help but giggle at them. And he was one seriously strange guy.

His real name was John. He was a six and a half foot tall bone skinny young dope addict with long greasy hair and a face marred by a moonscape of thick blackheads and craggy pockmarks. He was a sweet kid, but clearly his pilot light had gone out, if it had ever been lit. He was this weird kind of pathological shit-talker whose stories were lifted right out the plots to ‘80s B-movies. I mean we're talking car chases and super human fights with six and seven cops and swallowing pounds of dope without dying. It was so outlandish you simply couldn't believe that anyone could spin such bullshit with a straight face, but he did so, with the straightest of faces.

Because of this, none of us were exactly sure why he was in jail. He spun a dozen different versions of his arrest, and never was precisely clear on what the charges were against him. And it was me they thought was a cop.

The four of us-me, Lane, Soul, and "22"-formed an impromptu neutron crew and spent most of our time together. We would eat together underneath the stairs outside our cells and trade food and cigarettes within our own little trading bloc so we didn't have to beg or trade with the thugs, which invariably came back to haunt you later.

Soul and "22" had between them an entire lock box full of junk food and cheap tobacco from the commissary, and they were generous to Lane and I. Commissary was ordered and delivered once a week if you were fortunate enough to have someone on the outside put money on your CCDOC account. Without commissary, the stay in County is much, much harder. It's just like not having any money on the street. You get the barest minimum to survive, and you are responsible for the rest. And there's a painful gap between what most people are used to, and the privation of the inmate.

As I mentioned, I was a vegetarian at the time, which meant that more often than not I went hungry. It also meant that I had food to trade. Every lunch was bologna sandwiches, so I would barter for bread, or the rare slice of cheese, in exchange for my meat. The stench of the bologna was impossible to avoid, though, and the bread and cheese would be slimy with it. I gagged it down when I could. Dinner, the only real meal of the day, was hit or miss. The food was almost always edible, but definitely nasty. It was mass produced stuff, like beans and rice, or some goopy beef concoction. But they would often screw up the preparation and the food would be inedible. One beef and rice dish they gave us had so much salt in it people choked as they tried to swallow it.

We were all surprised on July 4th, though, because they were two hours late with dinner, but then showed up with baked chicken, an unheard of luxury. Even I ate the chicken, and paid for it later as it suddenly began to make sense to me how they could afford that much "fresh" chicken.

On the other side of my cell was King who came to Chicago from Mexico at age fifteen after his uncles, in some south-of-the border gang beef, murdered his father. They had wanted to take King and make him work for them, as a slave, as payment for his father's transgressions. Somehow King escaped and came across the border illegally. Though he says he came here to avoid gang life, that's precisely what he ended up in. When I asked him why he did it, he told me it was because he was 15 and dumped in an American city where he didn't speak the language and had no family. Mexicans base everything on the family, he said, so no one would help him get work or take him in. It was the gang, or homeless in the streets. The gang permitted him to survive; the streets would have consumed him.

King was bald with a goatee and covered in tattoos, handsome in the traditional sense. He spoke very seldom, and when he did, softly, preferring to spend a lot of time working out with Frosty. It had been ten years in the gang for him, and he would talk about retiring on his own terms. I asked him how often that really happened, and he said a lot more than is talked about.

Despite this horrific past, King was surprisingly peaceful, and even somewhat playful in a childlike manner. He spoke truth to power, without hesitation, about things he had to do to survive, and you saw that he was capable of tearing you apart if he had to, which was humbling. But he was generally a gentle person. The other cats on the deck paid him full respect. No one dared fuck with him.

Unlike many of those around me, who could go off at any second given the proper provocation, King's power was tempered by the knowledge that he wouldn't ever flex it unless he had to, so just don't ever give him a reason. Mexicans, he told me, have a certain honor about their violence. They don't start something unless they absolutely have to, but if they do, they go all out until they finish it.

It was different from the way the blacks and Puerto Ricans dealt with each other. They seemed to look for trouble and were always getting into shit over pride and bravado. They had a built in hatred that was incendiary. The Mexicans were too new to the city to have the history the other two did with each other. But they were coming so fast, soon they would be contending for power on a citywide scale. Half a million migrated to Chicago in the last ten years alone.

King's most gracious gift to me was the "jailhouse hack," a ceaseless free floating viral infection that is like the human version of "kennel cough" in that it usually makes appearances in crowded institutional settings like this. It hits both the upper and lower respiratory system at the same time. You can't breathe because your face is painfully swollen and you are hacking up mucus globs the size and composition of Rock Island oysters. The hack never quite goes away completely. Within days I would contract it too, probably from sharing cigarettes with him, and it would haunt me for the next month as I moved from the County into the penitentiary system to serve out my sentence.

I was slated to ship out to the Stateville "reception and classification center," the entry point for the Illinois prison system, on a Friday morning. I was woken up at 3:30 by the unit C.O. who told me to "pack my shit" and be ready to go in ten minutes. I fumbled out into the day room to find Frosty sitting at one of the picnic tables, making instant coffee.

"You shippin' now, Chuck?"

"I am. Time to face the Beast."

"Shit, this is the Beast," he said, motioning around him. "You got gravy now. At least you gonna eat."

It was strange to think of a year in the penitentiary as "gravy," but it said a lot about what a shithole County was.

"When you get out, you gotta call me," Frosty said, slipping me a piece of loose-leaf paper with his name, address, and a couple phone numbers scribbled across it. "I got this idea for a play, and I want you to help me write it."

"Sure, that would be interesting," I said, not knowing if I meant it. My stomach was flopping around my innards. I had no idea what lay in store for me.

"I'm tellin' you, Chuck. I can be the next Tyler Perry. I saw that man on Oprah. He was homeless, and now he worth $90 million dollars! I said, shit, I got stories to tell. Lemme get some of this money."

"I know you do," I said, and clearly he did have stories, and the odds were that they would never be told.

At one of the picnic tables "The Reverend" was seated with one of his regular acolytes. Each had a bible open before him. They would get up like this every morning and come out to read their bibles and dissect scripture verse by verse in a way you never saw done in white churches. I have no idea whether he was speaking truth or just making it up as he went along. You never knew with jailhouse preachers.

I shuffled across the day room floor, and they both looked up at me as I passed close.

"Shipment?" Rev said.

"Yup."

"Can I pray for you, now, before you go?"

Before I could think about it my mouth said, "Sure." I figured it couldn't hurt.

Rev and his student led me down the stairs to the lower level and over into a corner where they normally held prayer circles. We three joined hands and lowered our heads and the Reverend began to pray for me, asking god to guide me and protect me and give me wisdom so that I may survive my ordeal and live to help others. When he finished, they both opened their eyes and looked at me. The Reverend continued.

"We are warriors, and we find ourselves in a time of war. You have been sent to serve this cause, and you know what we are up against, what they will do to their own people to achieve their goals?"

I nodded.

"Always remember that. Remember who they are, whenever you are faced with a difficult decision. And remember...all is forgiven. The past is behind you. Pay no mind to anyone who wishes to focus on that. You have a responsibility now. Your life is this moment forward."

Understand, this was the first time I had ever spoken to either of them. Even in the most benign interpretation it was clear that the Reverend had quietly been listening to me blather on about race and prison and the drug war and the government. Something in what I had said connected with him and so he spoke back directly to my heart in a way that made me believe he sensed exactly what I was feeling at that moment and wished to help quell my fears and face the unknown with dignity. However, for me, a more esoteric interpretation was self-evident as The Reverend gazed deep into my eyes, you know exactly what I mean streaming from his countenance. The journey begins.